(an appropriation and erasure)

Monthly Archives: November 2021

Dine with Swine

(erasure from Mrs. Beeton’s Dictionary of Every-Day Cookery by Isabella Mary Beeton)

‘rhubarb’ by Tom Jenks – Beir Bua Press

I’ve known and enjoyed the work of Tom Jenks for a few years – both his output as editor/publisher of literary objects imprint zimZalla (two reviews here and here) and as writer of gloriously distinctive prose poetry. Before rhubarb I have enjoyed his and Catherine Vidler’s constraint construction Pack My Box with Five Dozen Liquor Jugs, a playful ‘zany and zanier’ collaboration (see details here) – though its undoubted cleverness is framed still in a way the writing in rhubarb isn’t.

rhubarb, from the wonderful and prolific experimental Beir Bua Press, is a ‘collection of a number of pieces written over a number of years’ and it has been interesting to trace what appears to be a range of styles built around a fundamental oblique and surreal world of Jenks’ writing.

I must, however, immediately challenge my dual categorising of this: neither is quite right, and ‘surreal’ has of late acquired an assault on its suggestiveness, usually by sportspeople interviewed on TV who have just achieved significant success and acknowledgement through their literal skills and dedication who still describe this as ‘surreal’ (when it is patently, and brilliantly, absolutely real). Therefore, I’d have to add/qualify that his writing is inventive, quirky, constantly surprising and signature.

I know best these signature prose poems that I encounter on social media postings, always happy to come across by chance and know I will definitely enjoy, smiling immediately at that first and then subsequent poetic shifts into the unexpected and unique.

The title poem of this collection takes us into a rhubarb world of ‘classic’ Jenks’ knowing, giving the vegetable a life beyond most of our imaginings, and introducing Stanley who knows even more. The ingredients, for example, of a ‘neutralising cordial’ involving rhubarb are revealed with the clarity of this further fascinating knowing.

The opening poem eyebrows exemplifies from the off the ‘peculiar’ narrative journeys we take as readers. Its first two stanzas

‘When I return from my walk across the fields,

my mother trims my eyebrows with the kitchen scissors.

They grow two centimetres every day.

The air is fertile out here in the country.’

launch us toward the sublime concluding visual of the curate ‘on his bicycle’ and the condition of his eyebrows. An ‘overlooked nineteenth century Russian novelist’ is the subject of the poem not so far, Fyodor and it is a tragedy, truly.

In when it gets dark, I fetch my special spoon we learn about the curing potency of UHT milk and a sponge as well as the connection (with Christmas approaching?) to ‘goose fat and memories’.

The poem hedge in its entirety speaks volumes about passion

‘We have planted a hedge at the edge of the fields. It grows a little

each day, like an ardour. At night we stand either side of it and

picture it seven feet tall, with a ditch.’

Where would you, as reader, imagine these opening lines from song from a forest will take you

‘What can I do with him, he is so randy,

hairy hands in the mayonnaise.’

I am wondering on behalf of Michael Bolton, by the way.

There is a comparative longpoem core in this collection Walt Disney is sending us letters, and it intrigues by sustained revelations that are absurd and comic and disturbing. There is a knight and there is WD and are either likely to be heroic?

There is another long and wise poem the baby that offers advice to those who anticipate and then have a baby. Surprisingly, there is some normal advice offered…

A favourite line from another poem:

‘I saw a dog that was entirely see through’

This brisk collection is an absolute delight. The storytelling is always fresh, and I have such huge respect for the imaginative depth with which Jenks sustains this. I’ve read many others who have tried to emulate – having a go myself – and speaking personally, it is upsetting to realise how impossible it is. I think of Matthew Sweeney and Ian Seed who also have their signature approaches in poetic narrative (as well as their failing imitators: OK, me again) and Tom Jenks is a bright light in that triumvirate.

Speaking of lights, I mentioned Christmas earlier. I know, it is only November, but it is near the end of the month. Two thoughts:

1.

It would make a wonderful Christmas game to choose and print opening and/or internal lines from any of these poems and put in a small box or other receptacle (a rhubarb basket perhaps) and family members and guests select and have to write the ‘rest of the story’ or similar from their randomly selected lines.

2.

Buy this book as a Christmas gift. Really. It would make a superb present; great Xmas reading. Fun and unusual, easy to cover in one sitting or a few. Tell readers they don’t need to take drugs to read and encounter amazing worlds; or encourage to take drugs and read and blow their minds beyond any previous hallucinogenic experience.

I am serious about both of these. More details and to purchase, go here.

On the Level

(erasure from The Pilgrims’ First Christmas by Josephine Pittman Scribner)

Kenosha

~

Castration at Times

With my thanks to International Times and Rupert for posting my poem here today, and with congratulations to IT on its 10th online anniversary.

NB it should read ‘two pricks…’

Horizon Event

1.

When lock

down

set the bar so

low

we could all be forgiven when not looking across that long distant line for genuine

hope.

2.

Is it still a better kind of expectation than being heroic? Another question: are there reasonable grounds for the unprecedented? Austerity has its own arc which is invisible but a boundary all the same. There has to be an ethos for recovery, a character that holds belief beyond the self and therefore appears to touch the sky. In an atmosphere of refraction, we all formalise different journeys, and communication becomes the gauge of our ability to arrive. Derivation on the curve, more or less. Approximation would appear to be the gaping hole in political argument, especially when leaders just guess, flip a coin, check discredited runes, or simply lie.

3.

There is

a dialogue with the past that

has to be had.

While horizons

remain the same in any era,

their narrative lines

are threads

that break or survive.

Bring Out

Your Dead,

Pile Them High

is an echo

spinning its

curve along the recurring event

of deaths,

but there are

nuances of whether we care

or not.

4.

Let us formalise the question: are the

gaping holes an ethos for being

unprecedented? Self-refraction flips

those runes to spin the heroic, but here

is an argument discredited on the grounds

of what is reasonable. Approximation is

derivation, a curve on the journey to the

boundary of belief, and the political is

invisible: all we own is communication,

and when this holds there is recovery.

Check expectation is more than a guess,

especially when the same as some lie,

and know austerity is more than less,

especially as we gauge an arc of sky.

5.

Hope in the offing

is more than a distant view

on the horizon:

when touch meets the sky

like a lyrical line, we

want meaningfulness.

The Revelation of ‘sweethearts’ by Emmett Williams

I have recently discovered the full/er story of Emmett Williams’ concrete poem/narrative sweethearts, this after nearly 40 years of ‘knowing’ it as something quite different.

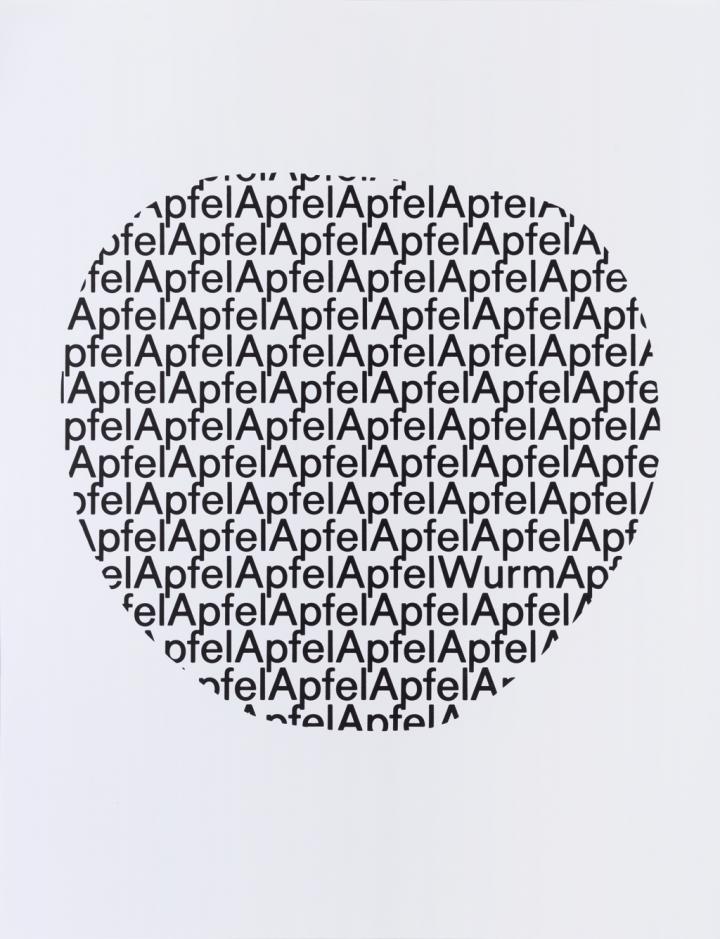

In the early 80s and at the beginnings of my English teaching career, I would introduce concrete poetry to students for reading enjoyment and their own creative writing. My models at that time were work by Edwin Morgan, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Eugen Gomringer, Ernst Jandl (the amazing Erschaffung der Eva), Claus Bremer, and Reinhard Döhl with the wonderful Aphel.

These writers and examples of their concrete poems were from an anthology – a print book – and I essentially knew just the ones provided for illustration, unable as we are today to explore widey online. Of course, I might have done more of this over the years than is the case, but I did so to some degree, and have more recently downloaded/collected a greater range – those familiars as well as new – and I am currently reading Concrete Poetry edited by Nancy Perloff: another print copy, but a fulsome history to hand.

I compiled my own booklet in the early 80s containing many of the above poems mentioned as well as others, and along with Emmett Williams’ superb like attracts like,

I included his sweethearts poem which at the time was comprised of the 5 pages I had. Thinking this the complete version, I presented it as a concrete poem narrative telling the story of sweethearts who have a fight and break up: quite an acceptable interpretation on my evidence, and certainly able to illustrate how the ‘grid’ formula of this concrete poem can work from simple to expansive. Here are the 5 pieces I had:

I only last week learned that sweethearts was published as a book of 226 pages in 1968; this in fact 138 pages of the actual sequence of concrete poems (I’m guessing – see link below – but this could still be an ongoing error), ‘starting’ with the single line sweethearts, and read from back to front where this singular line is, or in any formation the reader chooses: I like the full page/grid of sweethearts from which the rest is composed by erasures as its beginning. As it turns out, the complete text is a gloriously and at times explicit erotic poem, so my ‘version’ was acceptable for classroom use!

You can read online here.

‘From Fibs to Fractals. Exploring mathematical forms in poetry’ by Marian Christie – Beir Bua Press

In 1969 I gained a Grade 4 CSE in Maths – this, so I was told at the time, the average attainment for a 16-year-old, though in reality it was the average in the lesser tier that wasn’t an ‘O’ level (GCE), the qualification required for college and many jobs. Some years later, in gaining my teaching qualification, I also acquired the compulsory GCE maths ‘equivalent’, this having taken a multiple-choice test where, as an example, solving the quadratic equation question containing letters x and y was a cinch when only one of the 4 possible solutions contained these…

I have considered the above a full disclosure before writing this review.

Thankfully, Marian Christie’s book is a consummate lesson in explanation, clarity, illustration and considerable engagement – and thus wonderfully accessible to me regardless of previous aptitudes. That she has Masters Degrees in both Mathematics and Creative Writing informs the content, but one immediately realises it is her lifelong interests and experiences in both areas that conveys its deep understanding.

I’ll write about the book’s beginnings as a flavour of all it contains, my further reading a pleasing anticipation. The Introduction informs and persuades on the interconnectivity of mathematics and poetic skills – how the poet uses the former in writing, for example, a villanelle, and how the mathematician uses the latter in, for example, seeking ‘elegance of expression and clarity in lay out’. Some historical reference and illustration consolidate the facts and then agenda for the book.

We are quickly convinced of how these linked aspects are realised in ‘Fib poems’ – this the perfectly simple point at which I began to understand a seemingly more complex presentation of Fibonacci Poems in the first chapter. What Christie then moves on to demonstrate are the variations and alternatives there are in using and developing a Fibonacci sequence – how poets/writers are not necessarily constrained by an initial definition (though there is constraint inherently in the formula).

The second chapter Square Poems introduces the SATOR square – new to me – and its origins are both fascinating and meaningful in the ‘elegant ingenuity’ it presents for storytelling and the writer. It is important to stress how the effectiveness of this book is in its explanation and celebration of mathematical forms linked so quickly and engagingly to examples of their use in poetry. I was personally hooked with the first illustration by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson – pen name Lewis Carroll – because I have recently been appropriating his writings in Symbolic Logic for some of my found, experimental poetry.

Christie demonstrates how the square form can be seen in the 1597 poem by Henry Lok ‘in honour of Queen Elizabeth I’ – a compelling example of its intricate patterning – 10 lines, each containing 10 single-syllable words – and how it can be read in a variety of ways: the reader able to share in generating the experimentation. And as Christie says, ‘Clearly, experimental poetry was alive and well in Elizabethan times!’

Further examples of this technique/formatting are then shown in concrete and visual poetry with Bob Cobbing’s Square Poem. My use of teaching and writing square poems (or as I thought of them, grid poems) were influenced by work from Edwin Morgan, and it is a genuine learning curve to see its origins and broad uses over time so brilliantly presented here.

Only last week I wrote of how my ignorance continues to amaze me, this in discovering that my lifelong knowing of Emmett William’s poem Sweethearts at five pages (all I had ever seen, and used in my teaching) is actually a whole book of 226 pages! Seeking to rectify this wasn’t my prompt in getting Marian Christie’s book – rather its fascinating focus on maths in/and poetry – but it has so far proved as educational as it is appealing. I am so looking forward to reading the chapter Reflection Symmetry.

Further details and to purchase, go here.

Better Versions of Oneself

For all the mistakes I have made in the past

I will atone with a better version of myself

For all the versions I have been in the past

I will atone with a better range of mistakes